News

»The Serbian borders are heavily affected by pushbacks and police brutality«

Serbia stands as the final country along the so-called Balkan refugee route that lies outside the European Union, yet shares borders with four EU member states. In this context, we can witness efforts to fortify the external European borders. Milica Svabic, part of our partner organization klikAktiv, provides further insights into the situation.

Milica, at first: Who are you, who is klikAktiv and what are you doing?

My name is Milica Svabic. I’m a lawyer in Serbian organization called klikAktiv which provides free legal aid and psychosocial support to people on the move, asylum seekers and refugees in Serbia.

KlikAktiv was founded in 2014 as an organization for psychological and medical aid for homeless people. One year later, with the so-called refugee crisis on the Balkan, it shifted its activities towards people on the move.

KlikAktiv currently has six team members. Lawyers, project manager, social workers and cultural mediators. We don’t have a major donor and I think this is really good, because it keeps us independent. We get our funds from different foundations and organizations, mostly based in the European Union – as PRO ASYL. We are working together since January 2022.

In the last five years the majority of people who are stuck in Serbia don’t have access to asylum procedure and state protection in Serbia. So we are trying to reach those people, most often located at Serbian Northern borders, which are at the same time EU external borders.

So, how is the situation at the Serbian borders right now?

Serbia is the final non-EU country on the so-called Balkan refugee route. The majority of people continue to enter Serbia at the southern border, coming from the direction of Bulgaria. In recent months, however, the route via North Macedonia have become increasingly important. Last year, we also noticed an alarming increase in the number of pushbacks from Serbian territory. This increase corresponds with the presence of Frontex on this border.

Also, not only Frontex but other foreign police officers are present on the Serbian southern borders based on bilateral agreements.

For many years already, Serbian northern borders were heavily affected by pushback practices. This remains the case. We are documenting unlawful pushbacks and a lot of police violence at all four borders: the border between Bosnia and Serbia and the three EU external borders to Croatia, Hungary and Romania.

»Serbian government is following the far right policies like in other European countries as well – and they don’t actually want people to stay.«

You mentioned the presence of Frontex corresponds with increasing border violence – could you say in which ways?

So although Serbia is not a member of the EU, we have Frontex presence. Serbia signed the agreement with Frontex in 2019 and in 2021 the first Frontex officers came to Serbia. At the beginning, they were only present at the border between Serbia and Bulgaria. Over the time they gained presence at the border with North Macedonia and also on the Serbian northern borders. Until the end of October last year, the majority of people were trying to leave Serbia through Hungary. Then there was a huge shift in the route, now most people are exiting Serbia to Croatia and Bosnia-Hercegovina. When Frontex became present on the Serbian territory, we started seeing more pushbacks from the south, but also we started noticing more police violence on the north borders.

It’s very difficult to determine the involvement of Frontex in these unlawful operations. What we see on the ground is that Frontex officers are not properly marked, and often people on the move can not assign the perpetrators to a unit with certainty. However, very frequently we do hear about violence and pushbacks by foreign police officers who are present on the Serbian territory. But it’s difficult to establish whether they were present as part of Frontex mission or as part of bilateral agreements that Serbia has with these states.

How is the actual situation in the camps in the north?

Currently, all camps in the north of Serbia are closed. They were closed at the end of last year in December, after the big police action which started in October.

There has been a shooting between rival smuggling gangs and three people died – after that, the police operation began. While the level of violence has taken on new dimensions, the police operation was nevertheless directed against people seeking protection, who are themselves affected by this violence, and not primarily against the trafficking gangs. Before, there have been more than 35 informal settlements on the north of Serbia and three official state run camps. They all have been evicted. It’s unclear why they evicted the official camps as well but there is not a single person left there at the moment.

They seem to expand the capacities there now. We heard several rumours and different stories of what might happen with those camps. One of them is that it might serve to accommodate people who will be returned from the neighbouring member states, based on readmission agreement. Other rumours are that they might serve as EU transit camps on foreign soil in the future or as national detention centers.

Where did the people living in those camps go to?

People were transferred to the camps in the south. Unfortunately, also many people were kept in detention center and in general jails for the offense of illegal residency, and it’s very likely that many people were also pushed back to Bulgaria and North Macedonia.

Those camps in the south, how is the situation there?

When this police action started at the end of October, all of the camps were over the capacity and they were quite full. And for a few days people were not allowed to leave the camps. We know that Serbian police, together with Europol, was present in all of the camps and they took the fingerprints and personal data of people. It’s unclear for what purpose and who will have access to this data. After a few days, camps were open and people were allowed to move freely. Majority of people at that time left towards Bosnia and Hercegovina – and what we hear from people is that they were also encouraged by the Serbian police to take this route. As a result, the situation in the camps has eased and they are no longer overcrowded.

So on one side, Serbian police is playing a good partner to the EU, showing that they will keep people on the Serbian territory. But on the other side, Serbian government is following the far right policies like in other European countries as well – and they don’t actually want people to stay. So we also see the encouragement of the Serbian police and Serbian government to push people further to the Western Europe.

Which problems can be observed in the official camps in general?

Serbia has 19 state run camps. According to the law, people can be accommodated in the camps only if they’re asylum seekers and the police are the body that should refer an applicant to a specific camp. However, in practice, Serbia has developed the narrative of being a transit country, this is leading Serbia’s policy. So camps are deemed to serve as temporary accommodation only. This creates great confusion and ultimately leaves protection seeking people without official status and support in Serbia.

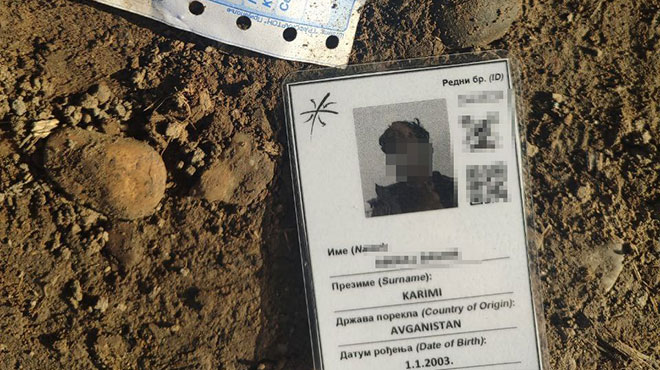

In practise, people on the move go directly to a camp where then a registration is done by the camp management – but it’s practically a fake registration. They take people’s fingerprints, pictures, and personal information. People are then issued what is called a »camp card«. It is a small piece of paper with their picture and personal information. But again: this document is not proclaimed by law, but it makes people believe that they have applied for asylum and that they have regulated their residency in Serbia. There is no referral to the office actually responsible for the asylum application. Very often people are being kicked out from the camps after some days and left without any access to help. At the same time, criminal traffickers are present in both the informal and formal camps.

In my opinion, this is one of the biggest problems in the Serbian camps. But also violence, which was increasingly reported in the last few months, both by state institutions as well as by criminal groups in the official camps, is a major concern.

You say that smuggling gangs are active both outside the official camps but also inside?

Yes. It’s very clear that some of the people who are in Serbia for a very long time have privileged position in the camps. And it’s quite visible that the state and the Commissariat for refugees and migration, which runs the official camps, are quite supportive of these criminal groups. Again, they understand Serbia as a transit country, and these groups are »helping« people leaving Serbia. It’s been communicated quite often in the informal meetings that the only way how people can actually leave Serbia is with the help of smugglers and criminal groups. Next to this, of course, over the past years we have also seen many cases of corruption and bribery in the official camps.

Overall, Serbia is also trying to prevent access to the proceedings. But in theory, how should the asylum procedure actually work from a legal point of view?

In theory, it is possible to get asylum in Serbia, but in practice it is quite hard. Serbia first established its national asylum system in 2008 and from 2008 until today less than 250 people got asylum, which is an extremely low recognition rate. The asylum procedure is very bureaucratic, and it’s quite difficult to have access to it.

»The police is doing everything possible to enable people from entering asylum procedure.«

An application for asylum should be lodged with a police station. In the majority of cities, however, the police refuses to register people for asylum. Instead, the police regular issues expulsion orders, which prevent a later application for asylum. Hence, the police is doing everything possible to enable people from entering asylum procedure.

For example, there was this woman from Mongolia. A single mother of five children. She was stuck in one of the informal settlements, where she was heavily pressured by criminal groups to pay additional money in order to take her across the border. She decided to apply for asylum in Serbia. We supported her and accompanied her to two police stations in the Serbian north. We informed the police via email that she will arrive, about her vulnerable position and said that she wants to apply for asylum in Serbia. However, she was kicked out from both police stations, and they refused to register her. At the end she went to one of the official camps, but was not properly registration – which means that she could not file the asylum application. She stayed there for two weeks and then she disappeared. We can assume that she went back to the criminal groups.

Very, very few people actually do manage to apply for asylum, usually with the assistance of local NGOs. And then the procedure is very, very long. It takes around one year for people to get a decision in average. Very often, the first decision is negative, so then you have to appeal, and the appeal process can last even longer. Some people are in the process for more than ten years, waiting for a positive decision. All of this is quite discouraging – and this is the reason also why many people don’t see Serbia as a final country and move towards other countries in Europe.

You mentioned the »expulsion orders«. What is that?

An »expulsion order« is an administrative decision issued by the Ministry of Interior, which says that the person doesn’t have a legal residency in Serbia and gives them a certain amount of time to leave Serbia on a voluntary basis. In case you don’t obey by the orders of the Ministry of Interior, you can be forcefully returned to the country of origin.

And with such an expulsion order, you are not allowed to apply for asylum?

Yes, exactly. If you get an expulsion order, you cannot apply for asylum any longer. The Ministry of Interior interprets this as a misusage of asylum, saying that you are actually applying for asylum only to prevent deportation and force removal to the country of origin.

Already earlier, you mentioned “readmission agreements” which serve as ground for returning people to Serbia. So there are agreements with EU member states to take refugees back?

In practical terms, yes. But officially it looks a bit different. Serbia has a readmission agreement with the EU from 2007 and article 3 of this readmission agreement says that Serbia can take third country nationals from the territory of neighbouring member states if the person has entered the member state directly from the territory of Serbia in the last two years or three years. Even though refugees and asylum seekers should remain unaffected, they also fall victim to this practice. This is quite often used by the neighbouring member states.

We collected material, proofs and testimonies of people being returned from Romania, from Croatia or from Hungary as well. In practice, if a person just says that he or she entered the member state from Serbia, this will be enough for those Member States to return them back. And in Serbia they don’t have the access to asylum again.

This is also one of the biggest issues in the negotiations for Serbia to join the European Union. It’s always emphasized that Serbia should admit more third country nationals based on readmission agreements. And this is something that we do see is happening in practice. However, this is, again, the double standards that the Serbian government has on one side, people are taken back but on the other side, don’t allowed to apply for asylum, they don’t get support or protection – so they will try to get to the European Union again.

Referring to the Serbian society, there are a lot of people with an own refugee story. How is their opinion on refugees and their situation in Serbia? Is there an active civil society in this regard?

The people without an own refugee history have the same narrative towards the refugees today as they had in the 1990s towards the refugees from Bosnia and Croatia: »The refugees came to take our land, our houses, our jobs«. So even towards the refugees from Bosnia and Croatia – and those were people who spoke the same language, had the same religion, went through same education programs – the people in Serbia had a negative attitude.

Unfortunately, when we are talking about people who have refugee experience themselves, who are originally from Bosnia and Croatia, and now they live in Serbia, very often you will get this similar negative narrative about the refugees from Syria and Afghanistan and other countries even there.

But there is also a network of civil society organizations which is supporting people on the move, asylum seekers and refugees. Unfortunately, the majority of those civil society organizations has only one bigger donor, usually the UNHCR or IOM, which means that then they have to follow the policy of these big international donors. That’s why we are happy to be very independent.

Thank you very much, Milica!

klikAktiv is a Serbian NGO based in Belgrade. The team offers free and independent legal advice and psychosocial support for people seeking protection in Serbia. The team regularly travels to Serbia’s EU borders and documents the human rights situation of people seeking protection there. The organization has been supported by the PRO ASYL Foundation since 2021.

(Interview: mk)